There is common misconception that troubles most developers using PostgreSQL: tune VACUUM or run VACUUM, and your database will stay healthy. Dead tuples will get cleaned up. Transaction IDs recycled. Space reclaimed. Your database will live happily ever after.

But there are couple of dirty "secrets" people are not aware of. First of them being VACUUM is lying to you about your indexes.

The anatomy of storage

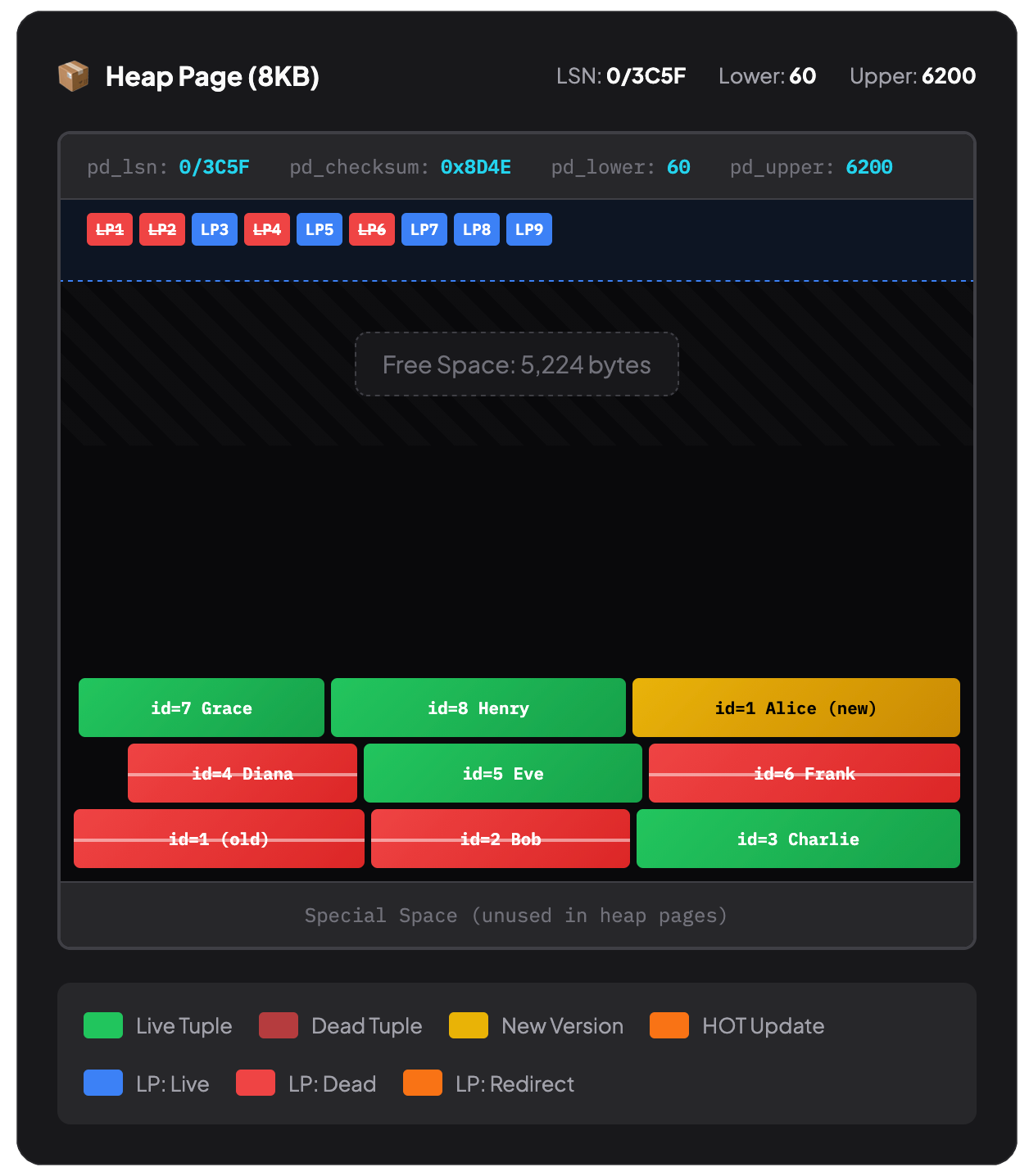

When you delete a row in PostgreSQL, it is just marked as a 'dead tuple'. Invisible for new transactions but still physically present. Only when all transactions referencing the row are finished, VACUUM can come along and actually remove them - reclamining the space in the heap (table) space.

To understand why this matters differently for tables versus indexes, you need to picture how PostgreSQL actually stores your data.

Your table data lives in the heap - a collection of 8 KB pages where rows are stored wherever they fit. There's no inherent order. When you INSERT a row, PostgreSQL finds a page with enough free space and slots the row in. Delete a row, and there's a gap. Insert another, and it might fill that gap - or not - they might fit somewhere else entirely.

This is why SELECT * FROM users without an ORDER BY can return rows in order

initially, and after some updates in seemingly random order, and that order can

change over time. The heap is like Tetris. Rows drop into whatever space is

available, leaving gaps when deleted.

When VACUUM runs, it removes those dead tuples and compacts the remaining rows within each page. If an entire page becomes empty, PostgreSQL can reclaim it entirely.

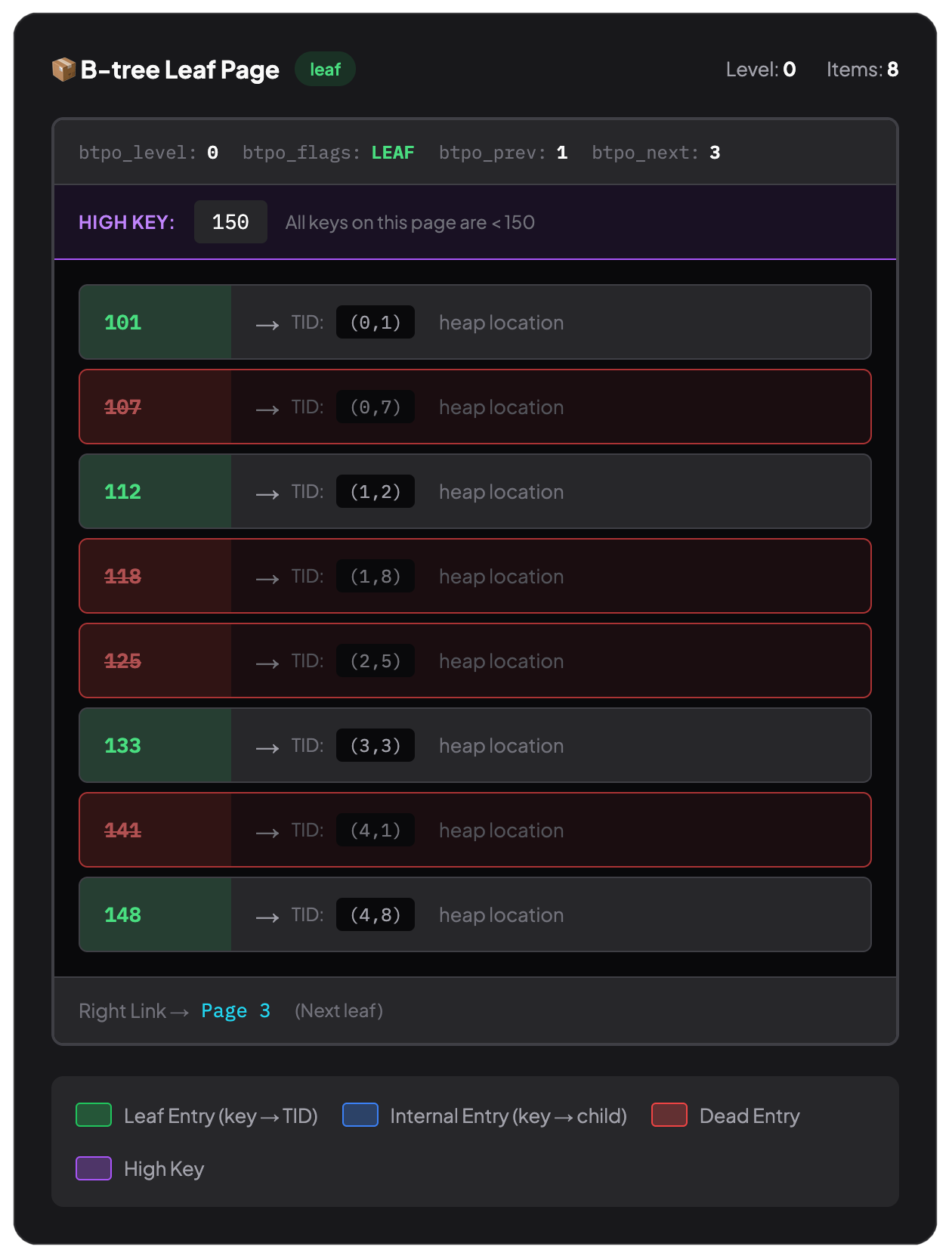

And while indexes are on surface the same collection of 8KB pages, they are

different. A B-tree index must maintain sorted order - that's the

whole point of their existence and the reason why WHERE id = 12345 is so

fast. PostgreSQL can binary-search down the tree instead of scanning every

possible row. You can learn more about the fundamentals of B-Tree Indexes and

what makes them fast.

But if the design of the indexes is what makes them fast, it's also their biggest responsibility. While PostgreSQL can fit rows into whatever space is available, it can't move the entries in index pages to fit as much as possible.

VACUUM can remove dead index entries. But it doesn't restructure the B-tree. When VACUUM processes the heap, it can compact rows within a page and reclaim empty pages. The heap has no ordering constraint - rows can be anywhere. But B-tree pages? They're locked into a structure. VACUUM can remove dead index entries, yes.

Many developers assume VACUUM treats all pages same. No matter whether they are heap or index pages. VACUUM is supposed to remove the dead entries, right?

Yes. But here's what it doesn't do - it doesn't restructure the B-tree.

What VACUUM actually does

- Removes dead tuple pointers from index pages

- Marks completely empty pages as reusable

- Updates the free space map

What VACUUM cannot do:

- Merge sparse pages together (can do it for empty pages)

- Reduce tree depth

- Deallocate empty-but-still-linked pages

- Change the physical structure of the B-tree

Your heap is Tetris, gaps can get filled. Your B-tree is a sorted bookshelf. VACUUM can pull books out, but can't slide the remaining ones together. You're left walking past empty slots every time you scan.

The experiment

Let's get hands-on and create a table, fill it, delete most of it and watch what happens.

CREATE EXTENSION IF NOT EXISTS pgstattuple;

CREATE TABLE demo (id integer PRIMARY KEY, data text);

-- insert 100,000 rows

INSERT INTO demo (id, data)

SELECT g, 'Row number ' || g || ' with some extra data'

FROM generate_series(1, 100000) g;

ANALYZE demo;At this point, our index is healthy. Let's capture the baseline:

SELECT

relname,

pg_size_pretty(pg_relation_size(oid)) as file_size,

pg_size_pretty((pgstattuple(oid)).tuple_len) as actual_data

FROM pg_class

WHERE relname IN ('demo', 'demo_pkey');relname | file_size | actual_data

-----------+-----------+-------------

demo | 7472 kB | 6434 kB

demo_pkey | 2208 kB | 1563 kBNow remove some data, 80% to be precise - somewhere in the middle:

DELETE FROM demo WHERE id BETWEEN 10001 AND 90000;The goal is to simulate a common real-world pattern: data retention policies, bulk cleanup operations, or the aftermath of a data migration gone wrong.

VACUUM demo;

SELECT

relname,

pg_size_pretty(pg_relation_size(oid)) as file_size,

pg_size_pretty((pgstattuple(oid)).tuple_len) as actual_data

FROM pg_class

WHERE relname IN ('demo', 'demo_pkey');relname | file_size | actual_data

-----------+-----------+-------------

demo | 7472 kB | 1278 kB

demo_pkey | 2208 kB | 313 kBThe table shrunk significantly, while index remained unchanged You now have 20,000 rows indexed by a structure built to handle 100,000.

But notice something important: even though actual_data dropped to ~1.3 MB

(reflecting our 20,000 remaining rows), the file_size for the index is still

2208 kB. VACUUM cleaned out the dead tuple data, but it doesn't return space to

the OS or compact index structures - it only marks pages as reusable within

PostgreSQL.

EDIT: the original table had a size without running VACCUM, which I must left out during what's sometime cumbersome process of authoring blog posts. Big thanks come to Creston Jamison of Scaling PostgreSQL to notice it, and actually take what must have been a lot of time to analyze my posts.

This experiment is really an extreme case, but demonstrates the problem.

Understanding page states

Leaf pages have several states:

Full page (>80% density), when the page contains many index entries, efficiently utilizing space. Each 8KB page read returns substantial useful data. This is optimal state.

Partial page (40-80% density) with some wasted space, but still reasonably efficient. Common at tree edges or after light churn. Nothing to be worried about.

Sparse page (<40% density) is mostly empty. You're reading an 8KB page to find a handful of entries. The I/O cost is the same as a full page, but you get far less value.

Empty page (0% density) with zero live entries, but the page still exists in the tree structure. Pure overhead. You might read this page during a range scan and find absolutely nothing useful.

A note on fillfactor

You might be wondering how can fillfactor help with this? It's the setting you can apply both for heap and leaf pages, and controls how full PostgreSQL packs the pages during the data storage. The default value for B-tree indexes is 90%. This leaves 10% of free space on each leaf page for future insertions.

CREATE INDEX demo_index ON demo(id) WITH (fillfactor = 70);A lower fillfactor (like 70%) leaves more room, which can reduce page splits when you're inserting into the middle of an index - useful for tables random index column inserts or those with heavily updated index columns.

But if you followed carefully the anatomy of storage section, it doesn't help with the bloat problem. Quite the opposite. If you set lower fillfactor and then delete majority of your rows, you actually start with more pages, and bigger chance to end up with more sparse pages than partial pages.

Leaf page fillfactor is about optimizing for updates and inserts. It's not a solution for deletion or index-column update bloat.

Why the planner gets fooled

PostgreSQL's query planner estimates costs based on physical statistics, including the number of pages in an index.

EXPLAIN ANALYZE SELECT * FROM demo WHERE id BETWEEN 10001 AND 90000;QUERY PLAN

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

Index Scan using demo_pkey on demo (cost=0.29..29.29 rows=200 width=41) (actual time=0.111..0.112 rows=0 loops=1)

Index Cond: ((id >= 10001) AND (id <= 90000))

Planning Time: 1.701 ms

Execution Time: 0.240 ms

(4 rows)While the execution is almost instant, you need to look behind the scenes. The planner estimated 200 rows and got zero. It traversed the B-tree structure expecting data that doesn't exist. On a single query with warm cache, this is trivial. Under production load with thousands of queries and cold pages, you're paying I/O cost for nothing. Again and again.

If you dig further you discover much bigger problem.

SELECT relname, reltuples::bigint as row_estimate, relpages as page_estimate

FROM pg_class

WHERE relname IN ('demo', 'demo_pkey');relname | row_estimate | page_estimate

-----------+--------------+---------------

demo | 20000 | 934

demo_pkey | 20000 | 276The relpages value comes from the physical file size divided by the 8 KB page

size. PostgreSQL updates it during VACUUM and ANALYZE, but it reflects the

actual file on disk - not how much useful data is inside. Our index file is still

2.2 MB (276 pages × 8 KB), even though most pages are empty.

The planner sees 276 pages for 20,000 rows and calculates a very low rows-per-page ratio. This is when planner can come to conclusion - this index is very sparse - let's do a sequential scan instead. Oops.

"But wait," you say, "doesn't ANALYZE fix statistics?"

Yes and no. ANALYZE updates the row count estimate. It will no longer think you

have 100,000 rows but 20,000. But it does not shrink relpages, because that

reflects the physical file size on disk. ANALYZE can't change that.

The planner now has accurate row estimates but wildly inaccurate page estimates. The useful data is packed into just ~57 pages worth of entries, but the planner doesn't know that.

cost = random_page_cost × pages + cpu_index_tuple_cost × tuplesWith a bloated index:

- pages are oversized (276 instead of ~57)

- The per-page cost gets multiplied by empty pages

- Total estimated cost is artificially high

The hollow index

We can dig even more into the index problem when we look at internal stats:

SELECT * FROM pgstatindex('demo_pkey');-[ RECORD 1 ]------+--------

version | 4

tree_level | 1

index_size | 2260992

root_block_no | 3

internal_pages | 1

leaf_pages | 57

empty_pages | 0

deleted_pages | 217

avg_leaf_density | 86.37

leaf_fragmentation | 0Wait, what? The avg_leaf_density is 86% and it looks perfectly healthy. That's a trap. Due to the hollow index (we removed 80% right in the middle) we have 57 well-packed leaf pages, but the index still contains 217 deleted pages.

This is why avg_leaf_density alone is misleading. The density of used pages

looks great, but 79% of your index file is dead weight.

The simplest way to spot index bloat is comparing actual size to expected size.

SELECT

c.relname as index_name,

pg_size_pretty(pg_relation_size(c.oid)) as actual_size,

pg_size_pretty((c.reltuples * 40)::bigint) as expected_size,

round((pg_relation_size(c.oid) / nullif(c.reltuples * 40, 0))::numeric, 1) as bloat_ratio

FROM pg_class c

JOIN pg_index i ON c.oid = i.indexrelid

WHERE c.relkind = 'i'

AND c.reltuples > 0

AND c.relname NOT LIKE 'pg_%'

AND pg_relation_size(c.oid) > 1024 * 1024 -- only indexes > 1 MB

ORDER BY bloat_ratio DESC NULLS LAST;index_name | actual_size | expected_size | bloat_ratio

------------+-------------+---------------+-------------

demo_pkey | 2208 kB | 781 kB | 2.8A bloat_ratio of 2.8 means the index is nearly 3x larger than expected. Anything

above 1.8 - 2.0 deserves investigation.

We filter to indexes over 1 MB - bloat on tiny indexes doesn't matter that much. Please, adjust the threshold based on your environment; for large databases, you might only care about indexes over 100 MB.

But here comes BIG WARNING: pgstatindex() we used earlier physically reads the entire index. On a 10 GB index, that's 10 GB of I/O. Don't run it against all indexes on a production server - unless you know what you are doing!

REINDEX

How to actually fix index bloat problem? REINDEX is s straightforward solution as

it rebuilds the index from scratch.

REINDEX INDEX CONCURRENTLY demo_pkey ;After which we can check the index health:

SELECT * FROM pgstatindex('demo_pkey');-[ RECORD 1 ]------+-------

version | 4

tree_level | 1

index_size | 466944

root_block_no | 3

internal_pages | 1

leaf_pages | 55

empty_pages | 0

deleted_pages | 0

avg_leaf_density | 89.5

leaf_fragmentation | 0And

SELECT

relname,

pg_size_pretty(pg_relation_size(oid)) as file_size,

pg_size_pretty((pgstattuple(oid)).tuple_len) as actual_data

FROM pg_class

WHERE relname IN ('demo', 'demo_pkey');relname | file_size | actual_data

-----------+-----------+-------------

demo | 7472 kB | 1278 kB

demo_pkey | 456 kB | 313 kBOur index shrunk from 2.2 MB to 456 KB - 79% reduction (not a big surprise though).

As you might have noticed we have used CONCURRENTLY to avoid using ACCESS

EXCLUSIVE lock. This is available since PostgreSQL 12+, and while there's an

option to omit it - the pretty much only reason to do so is during planned

maintenance to speed up the index rebuild time.

pg_squeeze

If you look above at the file_size of our relations, we have managed to reclaim

the disk space for the affected index (it was REINDEX after all), but the table

space was not returned back to the operating system.

That's where pg_squeeze shines. Unlike trigger-based alternatives, pg_squeeze uses logical decoding, resulting in lower impact on your running system. It rebuilds both the table and all its indexes online, with minimal locking:

CREATE EXTENSION pg_squeeze;

SELECT squeeze.squeeze_table('public', 'demo');The exclusive lock is only needed during the final swap phase, and its duration can be configured. Even better, pg_squeeze is designed for regular automated processing - you can register tables and let it handle maintenance whenever bloat thresholds are met.

pg_squeeze makes sense when both table and indexes are bloated, or when you want automated management. REINDEX CONCURRENTLY is simpler when only indexes need work.

There's also older tool pg_repack - for a deeper comparison of bloat-busting tools, see article The Bloat Busters: pg_repack vs pg_squeeze.

VACUUM FULL (The nuclear option)

VACUUM FULL rewrites the entire table and all indexes. While it fixes

everything it comes with a big but - it requires an ACCESS EXCLUSIVE

lock - completely blocking all reads and writes for the entire duration. For a

large table, this could mean hours of downtime.

Generally avoid this in production. Use pg_squeeze instead for the same result without the downtime.

When to act, and when to chill

Before you now go and REINDEX everything in sight, let's talk about when index

bloat actually matters.

B-trees expand and contract with your data. With random insertions affecting index columns - UUIDs, hash keys, etc. the page splits happen constantly. Index efficiency might get hit at occassion and also settle around 70 - 80% over different natural cycles of your system usage. That's not bloat. That's the tree finding its natural shape for your data.

The bloat we demonstrated - 57 useful pages drowning in 217 deleted ones - is extreme. It came from deleting 80% of contiguous data. You won't see this from normal day to day operations.

When do you need to act immediately:

- after a massive DELETE (retention policy, GDPR purge, failed migration cleanup)

bloat_ratioexceeds 2.0 and keeps climbing- query plans suddenly prefer sequential scans on indexed columns

- index size is wildly disproportionate to row count

But in most cases you don't have to panic. Monitor weekly and when indexes bloat

ratio continously grow above warning levels, schedule a REINDEX CONCURRENTLY

during low traffic period.

Index bloat isn't an emergency until it is. Know the signs, have the tools ready, and don't let VACUUM's silence fool you into thinking everything's fine.

Conclusion

VACUUM is essential for PostgreSQL. Run it. Let autovacuum do its job. But understand its limitations: it cleans up dead tuples, not index structure.

The truth about PostgreSQL maintenance is that VACUUM handles heap bloat reasonably well, but index bloat requires explicit intervention. Know when your indexes are actually sick versus just breathing normally - and when to reach for REINDEX.

VACUUM handles heap bloat. Index bloat is your problem. Know the difference.