If you read previous post about buffers, you already know PostgreSQL might not necessarily care about your rows. You might be inserting a user profile, or retrieving payment details, but all that Postgres works with are blocks of data. 8KB blocks, to be precise. You want to retrieve one tiny row? PostgreSQL hauls an entire 8,192-byte page off the disk just to give it to you. You update a single boolean flag? Same thing. The 8KB page is THE atomic unit of I/O.

But knowing those pages exist isn't enough. To understand why the database behaves the way it does, you need to understand how it works. Every time you execute INSERT, PostgreSQL needs to figure out how to fit it into one of those 8,192-byte pages.

The buffer pool caches them, Write-Ahead Log (WAL) protects them, and VACUUM cleans them. The deep dive into the PostgreSQL storage internals starts by understanding what happens inside those 8KB pages. Pages that are used by PostgreSQL to organize all data - tables, indexes, sequences, TOAST relations.

The 8KB

DB_BLOCK_SIZE), though tablespaces with non-standard block sizes can be created separately.The 8KB page size can be traced down to original Berkley POSTGRES project created in mid-1980s. In those times Unix systems typically used 4KB or 8KB virtual memory pages, and disk sectors were 512 bytes. Choosing 8KB meant a single database page mapped cleanly to OS memory pages and aligned well with filesystem I/O.

And the math still works today. Modern Linux kernels manage memory in 4KB virtual memory pages. SSDs now use 4KB physical sectors instead of 512 bytes. The default filesystem block size on ext4 and XFS is 4KB. PostgreSQL's 8KB page still maps to two OS pages, two disk sectors, two filesystem blocks. The hardware changed underneath, but the alignment is still there.

But the choice isn't just about hardware alignment. It's a tradeoff between two opposing forces. Make the page size too small and you going to increase the overhead (page metadata being good example). Make it too large and you waste space and increase I/O requirements when you need a single narrow row.

The different situation is outside OLTP world. DuckDB, designed for analytical columnar workloads, uses 256KB blocks. When you're scanning millions of rows sequentially, the overhead-per-page penalty barely matters - you want big chunks to maximize throughput.

--with-blocksize at compile time. Some analytical workloads with wide rows benefit from 16KB or 32KB pages. But you'll need to rebuild everything from scratch, and unless you have a very specific reason and understand the downstream implications you almost certainly don't want to. The default works.

You can confirm the page size on any running instance.

SHOW block_size;

block_size

------------

8192

(1 row)pageinspect

PostgreSQL comes with an extension called pageinspect that lets you read raw page contents from SQL. It is part of the contrib modules and available on most installations. Let's enable it and create a small test table:

CREATE EXTENSION IF NOT EXISTS pageinspect;

CREATE TABLE page_demo (

id integer GENERATED ALWAYS AS IDENTITY PRIMARY KEY,

title text NOT NULL,

created_at TIMESTAMPTZ DEFAULT CURRENT_TIMESTAMP,

value numeric(10,2)

);

INSERT INTO page_demo (title, created_at, value)

VALUES

('Ergonomic standing desk, oak finish', '2026-01-15 09:23:45+00', 549.99),

('Wireless mechanical keyboard', '2026-01-15 10:05:12+00', 189.00),

('Desk lamp', '2026-01-16 14:31:22+00', 45.00);We have three rows. PostgreSQL has written them into a single heap page. Let's look inside.

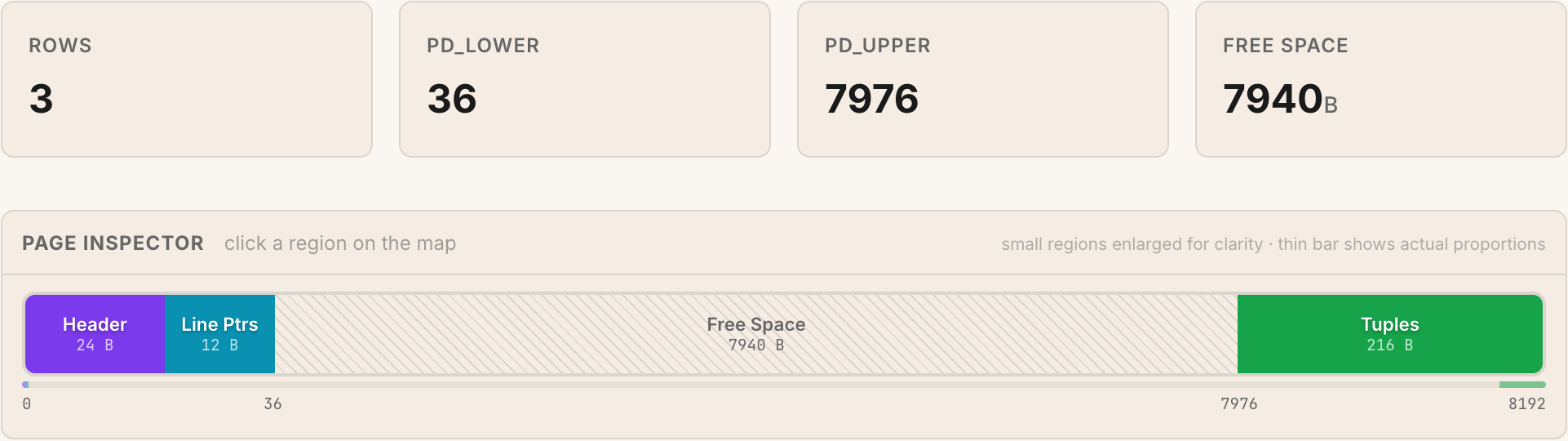

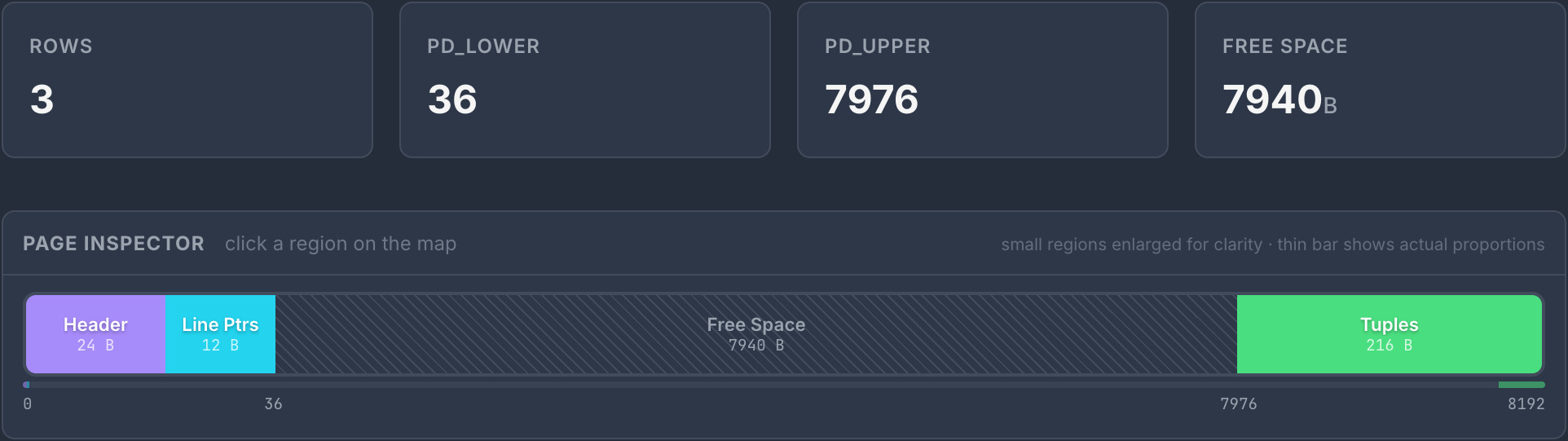

Reading a raw page header

The page_header function takes a raw page and returns the parsed header fields:

SELECT * FROM page_header(get_raw_page('page_demo', 0));-[ RECORD 1 ]---------

lsn | F/1F9ED410

checksum | 0

flags | 0

lower | 36

upper | 7976

special | 8192

pagesize | 8192

version | 4

prune_xid | 0Every one of those fields lives in the first 24 bytes of the page. Together they form the page header, and they tell PostgreSQL everything it needs to know about the page before touching any actual data.

The page header: 24 bytes of metadata

The first two fields are about safety, making sure the page survives crashes and silent corruption.

pd_lsn (8 bytes) the Log Sequence Number of the last WAL record that modified this page. During crash recovery, PostgreSQL compares this LSN against the WAL stream. If the WAL record's LSN is less than or equal to the page's LSN, the page is already up to date and the record is skipped. If it is greater, the record must be replayed. This single field is what makes crash recovery work.

pd_checksum (2 bytes) a checksum of the page contents. This is only active if the cluster was initialized with initdb --data-checksums (or checksums were enabled later with pg_checksums). When enabled, PostgreSQL verifies the checksum every time it reads a page from disk. A mismatch means silent data corruption, the kind that would otherwise go undetected until your data is wrong in ways nobody can explain.

Are checksums enabled on your cluster? Before PostgreSQL 17, they were off by default. Check with SHOW data_checksums;. If you see off on a production database, that's worth fixing. You can enable them retroactively with pg_checksums, though it requires a full shutdown.

PD_ALL_VISIBLEIndexes know what your data is, but not who is allowed to see it (in case a row was recently deleted or updated). Postgres has to do extra work to double-check the main table (the "heap") to ensure a row is visible.

When a page is marked PD_ALL_VISIBLE, it guarantees every row on that page is old enough to be seen by everyone. This lets Postgres skip the expensive heap check entirely and serve data straight from the index. A speed boost you may know as an Index-Only Scan.

The next fields are the page's spatial ma. They tell PostgreSQL where things are and where there's room for more.

pd_flags (2 bytes) bit flags that describe the page state. The important ones are: PD_HAS_FREE_LINES (are there any unused line pointers?), PD_PAGE_FULL (not enough free space for new tuple) and PD_ALL_VISIBLE (all tuples on page are visible to everyone).

pd_lower and pd_upper (2 bytes each) define the free space gap. pd_lower marks where the line pointer array ends -- in our output it is 36, that is 24 bytes of header plus 3 line pointers at 4 bytes each: 24 + (3 x 4) = 36. pd_upper marks where tuple data begins -- our value is 7976, meaning the three tuples together occupy bytes 7976 through 8191. Everything between these two offsets is free space. As you insert rows, these two values creep toward each other until there's no room left.

pd_special (2 bytes) the byte offset to the "special space" at the end of the page. For heap (table) pages, this equals the page size (8192), meaning there is no special space. For index pages, this area contains index-specific metadata.

pd_pagesize_version (2 bytes) encodes both the page size and the layout version number. The version is currently 4 for all modern PostgreSQL releases.

Finally, one field dedicated to cleanup.

Instead of waiting for a heavy VACUUM, Postgres can do garbage collection on the fly. When a normal query reads a page, it checks `pd_prune_xid`. If that transaction ID is older than all currently running transactions, the query instantly reclaims the dead space itself.

This is one of the cases where SELECT might modify data pages.

pd_prune_xid (4 bytes) the oldest transaction ID whose dead tuples have not yet been pruned from this page. When a new transaction accesses the page and finds that prune_xid is older than the global horizon, it triggers page-level pruning. A lightweight cleanup that reclaims space without a full VACUUM.

What is a line pointer?

If you're paying attention, we just mentioned line pointers in pd_lower description. If the page header discussed above is the general metadata, the line pointers (internally represented as ItemIdData) are the page table of contents.

Every time you insert a row, PostgreSQL doesn't just drop the raw data into the page. It actually splits the job into two steps.

- It puts the bulky, unpredictable row data (the tuple) at the very bottom of the page (more on this in the next section).

- It adds a tiny, fixed 4-byte line pointer right after the page header.

This pointer acts as a direct map. It holds exact byte offset and length of the tuple it points to. It allows PostgreSQL to only look at the offset and read the required number of bytes to get the tuple.

The line pointer array starts immediately after the 24-byte header and grows downward. Let's look at ours.

SELECT lp, lp_off, lp_flags, lp_len

FROM heap_page_items(get_raw_page('page_demo', 0)); lp | lp_off | lp_flags | lp_len

----+--------+----------+--------

1 | 8112 | 1 | 79

2 | 8032 | 1 | 77

3 | 7976 | 1 | 53Each line pointer is 4 bytes and contains three pieces of information:

- lp the ordinal position in the array (1-based). This, combined with the page number, forms the ctid - the physical address of a tuple. Row 1 on page 0 has ctid

(0,1). - lp_off the byte offset within the page where the actual tuple data begins. Notice the offsets decrease: 8112, 8032, 7976. Tuples are packed from the bottom up.

(0, 2), which means "page 0, line pointer 2". Because the index points to the pointer rather than the physical byte offset, Postgres can shuffle data or redirect pointers under the hood while the index reference remains perfectly valid.

- lp_flags the state of the pointer. The values are: 0 =

LP_UNUSED(available for reuse), 1 =LP_NORMAL(points to a live tuple), 2 =LP_REDIRECT(points to another line pointer, used after HOT pruning), 3 =LP_DEAD(the tuple has been determined dead but the pointer persists until cleanup). - lp_len the total length of the tuple in bytes, including the 23-byte tuple header, null bitmap, alignment padding, and actual column data.

The anatomy of a page

Here is how all these pieces fit together inside the 8KB block.

We already mentioned it above, but if you review the image carefully you can confirm the important insight. While line pointers are allocated downward from the header (pd_lower increases) the tuple data is stored upwards from the bottom of the page (pd_upper decreases). Free space is the gap between them.

This is called Slotted page layout and it's easy way how to prevent unnecessary data fragmentation. By storing predictable line pointers at top, they don't mix together with bulky and unpredicable tuples.

Free space: the gap in the middle

The free space on a page is the region between pd_lower and pd_upper. For our page:

SELECT lower, upper, upper - lower AS free_space

FROM page_header(get_raw_page('page_demo', 0)); lower | upper | free_space

-------+-------+------------

36 | 7976 | 7940

(1 row)With only three small rows, we have 7,940 bytes of free space. Almost the entire page is still available. Let's see what happens when we add more data:

INSERT INTO page_demo (title, created_at, value)

SELECT

'Generated item ' || i,

'2026-01-15 00:00:00+00'::timestamptz + (i || ' hours')::interval,

(i * 11.11)::numeric(10,2)

FROM generate_series(1, 10) AS i;

SELECT lower, upper, upper - lower AS free_space

FROM page_header(get_raw_page('page_demo', 0)); lower | upper | free_space

-------+-------+------------

76 | 7336 | 7260

(1 row)You can observe

pd_lowermoved from 36 to 76. Why? With 10 new line pointers at 4 bytes each we moved by 40 bytes.pd_upperdropped from 7,976 to 7,336. The 10 new tuples consumed 640 bytes of the data space.- And the free space shrank to 7,260 bytes.

How fast does a page fill up?

If we going to think about the page capacity, let's consider each row in this page costs:

- 4 bytes for the line pointer

- 23 bytes for the tuple header (transaction metadata, null bitmap offset, info mask)

- Alignment padding to the nearest 8-byte boundary after the header (1 byte of padding, bringing the header to 24 bytes)

- Actual column data: 4 bytes for the integer, variable bytes for the text, variable bytes for the numeric

For our new schema, each tuple is a bit larger than before. We saw earlier that our first 3 tuples took up exactly 216 bytes, which averages exactly 72 bytes per tuple. Add the 4-byte line pointer, and each row costs about 76 bytes of page space.

With 8,192 bytes in a page minus the 24-byte header, we have 8,168 bytes of usable space. At roughly 76 bytes per row, we can theoretically fit approximately 107 rows on a single page.

Let's test it. We already have 13 rows (3 original plus 10 generated). Let's insert more and check:

INSERT INTO page_demo (title, created_at, value)

SELECT

'Generated item ' || i,

'2026-01-15 00:00:00+00'::timestamptz + (i || ' hours')::interval,

(i * 11.11)::numeric(10,2)

FROM generate_series(11, 150) AS i;

SELECT count(*) AS tuples_on_page_0

FROM heap_page_items(get_raw_page('page_demo', 0));Total of 119 tuples fit on page 0 before PostgreSQL had to start using page 1. A bit more than our estimate of 107 -- the shorter generated titles take less space than "Ergonomic standing desk, oak finish".

The exact number always depends on column values, but this gives you a practical sense of capacity. Because this schema includes a variable-length text column, the row size flexes, but we still hit a very predictable ceiling right around 110-120 rows per 8KB block.

rows * average_row_size / 8192. But remember that "average_row_size" includes the 23-byte tuple header, alignment padding, and the 4-byte line pointer.

PostgreSQL's pg_column_size() function can help you measure actual row sizes.

Spanning multiple pages

With 160 rows in our table, we have started storing the tuples into a second page. Let's verify using the system catalog:

SELECT relpages, reltuples

FROM pg_class

WHERE relname = 'page_demo';relpages and reltuples values are estimates updated by ANALYZE and autovacuum. After bulk inserts, run ANALYZE page_demo; to refresh them.relpages | reltuples

----------+-----------

2 | 160

(1 row)Two pages. Let's insert substantially more data to see a real multi-page table:

INSERT INTO page_demo (title, created_at, value)

SELECT

'Generated row ' || i,

CURRENT_TIMESTAMP + (i || ' minutes')::interval,

(random() * 1000)::numeric(10,2)

FROM generate_series(1, 500) AS i;

ANALYZE page_demo;

SELECT relpages, reltuples

FROM pg_class

WHERE relname = 'page_demo'; relpages | reltuples

----------+-----------

6 | 660

(1 row)Six pages now. Each page is an independent 8KB block with its own header. Let's confirm by reading the headers of the first two:

SELECT 0 AS page, lower, upper, upper - lower AS free_space

FROM page_header(get_raw_page('page_demo', 0))

UNION ALL

SELECT 1, lower, upper, upper - lower

FROM page_header(get_raw_page('page_demo', 1)); page | lower | upper | free_space

------+-------+-------+------------

0 | 500 | 552 | 52

1 | 504 | 512 | 8

(2 rows)Both pages are nearly full, with only 52/8 bytes of free space remaining. Which is too little for another row to fit there.

The space that isn't there

You may have noticed that pd_special equals 8192 for our heap pages. The same size as the entire page size. I.e. there's no special space allocated.

This applies to the heap pages. But not all pages are heap pages. Index pages use the special space at the end of the page to store index-specific metadata. For a B-tree index, it includes pointers to sibling pages (for range scans), the tree level, and flags about the page type (leaf, internal, root, deleted).

Let's peek at the primary key index that was automatically created for our table:

SELECT type, live_items, dead_items, avg_item_size,

page_size, free_size

FROM bt_page_stats('page_demo_pkey', 1); type | live_items | dead_items | avg_item_size | page_size | free_size

------+------------+------------+---------------+-----------+-----------

l | 367 | 0 | 16 | 8192 | 808

(1 row)The type is l for leaf page. And if we check its page header:

SELECT special FROM page_header(get_raw_page('page_demo_pkey', 1)); special

---------

8176

(1 row)The special space starts at byte 8176, giving us 16 bytes (8192 - 8176) of B-tree metadata at the end of the page. Heap pages have none; index pages rely on it.

Putting it all together

Let's close with a complete view of our page. We know the header, the line pointers, the free space, and the tuple data regions. Here is a summary query that shows all of it at once:

SELECT

'header' AS region,

0 AS start_byte,

23 AS end_byte,

24 AS size_bytes

UNION ALL

SELECT

'line pointers',

24,

lower - 1,

lower - 24

FROM page_header(get_raw_page('page_demo', 0))

UNION ALL

SELECT

'free space',

lower,

upper - 1,

upper - lower

FROM page_header(get_raw_page('page_demo', 0))

UNION ALL

SELECT

'tuple data',

upper,

special - 1,

special - upper

FROM page_header(get_raw_page('page_demo', 0))

UNION ALL

SELECT

'special space',

special,

8191,

8192 - special

FROM page_header(get_raw_page('page_demo', 0)); region | start_byte | end_byte | size_bytes

---------------+------------+----------+------------

header | 0 | 23 | 24

line pointers | 24 | 499 | 476

free space | 500 | 551 | 52

tuple data | 552 | 8191 | 7640

special space | 8192 | 8191 | 0

(5 rows)476 bytes of line pointers means 119 entries (476 / 4). 7,640 bytes of tuple data. 52 bytes of free space. And zero bytes of special space (it's heap page).

That is the entire PostgreSQL 8KB page. Twenty-four bytes of header tell PostgreSQL where everything is. Line pointers provide table of contents.